Scanning the Horizon(s) of Quantum Applications

As previously noted, quantum science and technologies, while nascent, are being leveraged within and across a variety of military applications to fortify extant capabilities, and forge others anew, an example of which being the newly announced Quantum and Battlefield Information Dominance (Q-BID) Critical Technology Area. In the near term, such applications — and threats posed by peer-competitors’ and adversaries’ use of — quantum technology are relatively easy to define. However, this should not instill a sense of laxity, nor exaggerated alarm in forecasting or readiness to develop flexible adaptive response(s). But it should reinforce the need for recurrent reality checks.

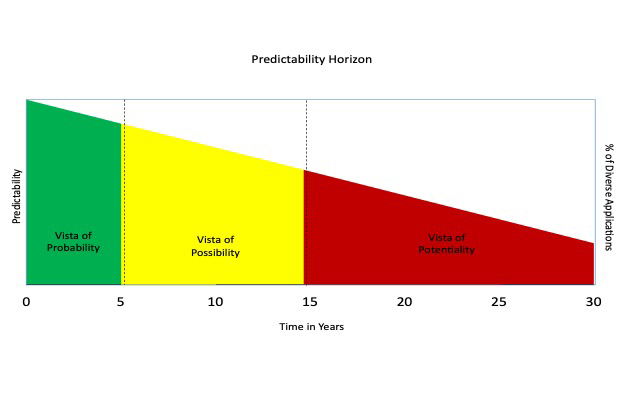

To bring this sense of reality into perspective, our ongoing work has defined three vistas of capability in which development and applications of technologies can evoke benefit, burden, risks and threats. As shown in Figure 1, below, these are the vistas of (1) probability (0-5 years; near-term); (2) possibility (6-15 years; intermediate); and potentiality (16-30 years; long-term). As illustrated in the figure (i.e., the left hand vertical axis), accuracy of prediction tends to decrease for more distally future events. To be sure, forecasting is easiest in the near-term; but speculation about what possibilities might arise from near-term probable events, and what potentialities might occur consequential to these possibilities is viable and can be fortified — and is thus recommended — through the use of (AI-enabled) modeling, tabletop exercises and war-gaming.

Figure 1

The Horizons of Predictability: Depiction of the inverse relationship of relative predictability, future time vista of use-in-practice, and percentage of diversity in applications of emerging technology

Taking these three horizons in turn, risk and threat posed by quantum technologies in the near-term (0-5 years) are strategic surprise via sensing in niche applications and faster-than-anticipated gain in adversary momentum in workforces and supply chains. While very much an element of research and industrial development competition, quantum computing is not sufficiently advanced to a technological level that affords readiness for immediate military utility.

In the intermediate-term (5-15 years), perhaps the most salient risk is the cryptographic transition gap. For example, the National Institute for Standards and Testing (NIST) has finalized core PQC standards (FIPS 203/204/205 published August 13, 2024), and the National Security Agency’s (NSA) CNSA 2.0 guidance anticipates transition of national security systems to quantum-resistant algorithms to be completed by 2035, with significant interim milestones achieved in sensing, networking equipment, operating systems, and cloud capabilities. Hence, the realistic risk is less a matter of “quantum will change everything” and more one of “we may fail to adapt and prepare at scale before our adversaries engage utility in the quantum technologies.” Accurate perception of capabilities, limitations and risk and threats is and will be essential to remain at tempo, if not ahead of peer-competitor and adversary enterprises in any disruptive technology; and that maxim is no different in the quantum space.

Long-term (16-30 years) risks are more difficult to predict (due to a phenomenon known as fractal diffusion: the fractal pattern-like variation in effects caused by reciprocally influential interaction and changes in diverse real-world variables over time); but one potential scenario might involve large-scale fault-tolerant computing systems that reshape cryptography, optimization, and simulation in ways that affect weapon design cycles, intelligence processing, and strategic stability. This would be particularly problematic in situations of asymmetric access to (advanced) quantum technologies and systems.

Biological Risks of Quantum Technologies?

So, while the risks and threats that quantum technologies pose in national defense and military contexts discussed thus far are short to intermediate term in their relevant exigency. A somewhat more intermediate to long-term risk posed by quantum technologies exists in the biological space. In this light, the practical question for joint warfighting is not whether “quantum will change biology,” but how quickly quantum-enabled performance gains or detriments could shift the tempo, reach, and concealability of biological threat development and deployment.

I foresee three major possibilities in this realm.

First, quantum computing and quantum-enabled simulation may compress timelines for molecular discovery. Even now, serious efforts are employing quantum methods to better model complex molecular interactions relevant to drug and peptide discovery. The dual-use implication is clear: the same innovations that accelerate therapeutics can be used to more efficiently identify and optimize bioactive compounds, including toxic ligands, enzyme inhibitors, or stability-enhanced proteins. This risk becomes greater given the convergence of quantum methods with advanced computational biology tools. Simply put, quantum acceleration is less about “inventing a new pathogen” and more about reducing impediments across the design–test–iterate cycle that historically have constrained development of sophisticated biothreats.

Second, quantum sensing affords a more granular, operationally relevant toolkit for detection and characterization of biological states. Quantum sensing enables accurate detection at lower signal levels, with greater portability, and through the use of novel modalities (e.g., magnetometry, nanoscale field sensing). While these may improve diagnosis and readiness monitoring, they also could enable covert biosurveillance, targeting of high-value personnel, discrimination of physiologic signatures (stress, fatigue, neurologic status), and/or improved assessment of exposure effects. Such capabilities could complicate counterintelligence and operational security by making the warfighters’ physiological states more observable at greater distances, and with smaller sensor footprints than current conventional sense-and-detect systems.

Third, quantum-secure communications and data practices are directly dually-usable. Discourses in the application of quantum systems in biomedicine characteristically emphasize data security and governance gaps as these technologies enter health ecosystems. However, the biosecurity risk is not only corruption or theft of medical data, but is also the possibility for strategic exploitation of sensitive force-health information for targeting, coercion, or influence; and, conversely, that an adversary’s quantum-secured data architectures would mitigate (if not completely prevent) our ability to surveille, detect or interdict illicit biotechnological research and development efforts that violate extant governances.

Recommendations for a (Realistic) DoW Quantum Posture

Given current realities and near-future possibilities, I advocate for the Department of War (DoW) to regard and treat quantum technologies as capability accelerators with dual-use applications and national defense consequences. Given the arc of near-term developments, horizon scanning should be yoked to measurable indicators of progress with biosecurity impact (e.g., qubit performance relevant to chemistry; quantum-sensing field trials, supply-chain diffusion of quantum platforms). Quantum-enabled scenarios should be integrated to biodefense exercises; and investments should include “secure biology” approaches (of oversight, doctrine and governance) that are commensurate with advances in computation and sensing that increasingly lower barriers to eliciting sophisticated biological effects. Toward these ends, I offer the following specific recommendations:

1. Quantum technology should be considered to be a readiness program-in-evolution, and not merely a cyber-upgrade. Accordingly, acquisition, zero trust, key management, and platform lifecycles should be aligned to NIST standards and NSA CNSA 2.0 milestones to prioritize “harvest-now, decrypt-later” security measures (e.g., long-life weapons systems data, HUMINT protection, sensitive SIGINT practices, etc.).

2. Quantum sensing should be exploited in those domains where readiness levels are most poised for mission use and measure operational effects and outcomes of its employment. Test-and-evaluation pathways should be developed that quantify performance in contested ecologies (e.g., GPS-degraded environments, electronic weapon-heavy theaters, and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR)-relevant scenarios) in order to identify and transition effective quantum systems’ applications into programs of record.

3. Quantum communications should be more realistically described so that investments reflect actual capabilities and constraints. Quantum networking research should be pursued in ways that avoid premature dependence on these technologies and systems for mission assurance until vulnerabilities and operational liabilities are addressed and resolved.

4. Mission focal quantum technology metrics and governance should be formalized and institutionalized to best implement the DoW Inspector General’s recommendations for annually updated service-informed lists of near-term quantum-relevant priorities. Funding should be directed at those priorities, and relevant benchmarks of progress should be monitored (in ways that more authentically represent operational viability and value, versus simple counts of available qubits).

5. The quantum supply chain and workforce should be treated as national defense assets vital to sustaining strategic leverage. Cleared talent pipelines should be fortified, fabrication and vendor ecosystems should be secured against IP leakage, given that adversarial intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance in this space are likely to be industrially and HUMINT-focused.

Conclusion

It is clear that quantum science and technology will contribute to future force capabilities, but not evenly, and surely not all at once. Near-term operational gains are most likely and credible in sensing and timing resilience, and proximate strategic risks are cryptographic transition and evolving utility in applications that may be applicable to other domains of effect and vulnerability (e.g., biology). Thus, I offer that present requirements are for (1) rational accounting of what quantum technologies are, and actually can and cannot do, and, based thereupon (2) disciplined governance that assesses quantum promise as operational advantage without succumbing to quantum mythology.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States government, Department of War or the National Defense University.

Dr. James Giordano is Director of the Center for Disruptive Technology and Future Warfare of the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University.